In February 1980, Black Hills Monthly launched its first edition by featuring Dick Termes on the cover with an article. Below is the text from the article as well as a PDF of the scanned issue.

If you think Spearfish. South Dakota is an ordinary town filled with ordinary folks, please close your eyes and conjure up a vision of Joseph Meier as the Christus high atop a life-size Calvary in the Black Hills. Now superimpose an image of Gary Muledeer Miller with his Three Mile Island haircut and a typewriter perched on his shoulder doing his version of the eleven o’clock news on Don Kirschner’s Rock Concert.

Yes, Spearfish partially nurtured both these geniuses. Mr. Meier made Spearfish his adopted home; Mr. Muledeer grew up in Spearfish and then left to find his fortune with Dina Shore and Woody Allen. But can Spearfish both raise a genius and hang on to one?

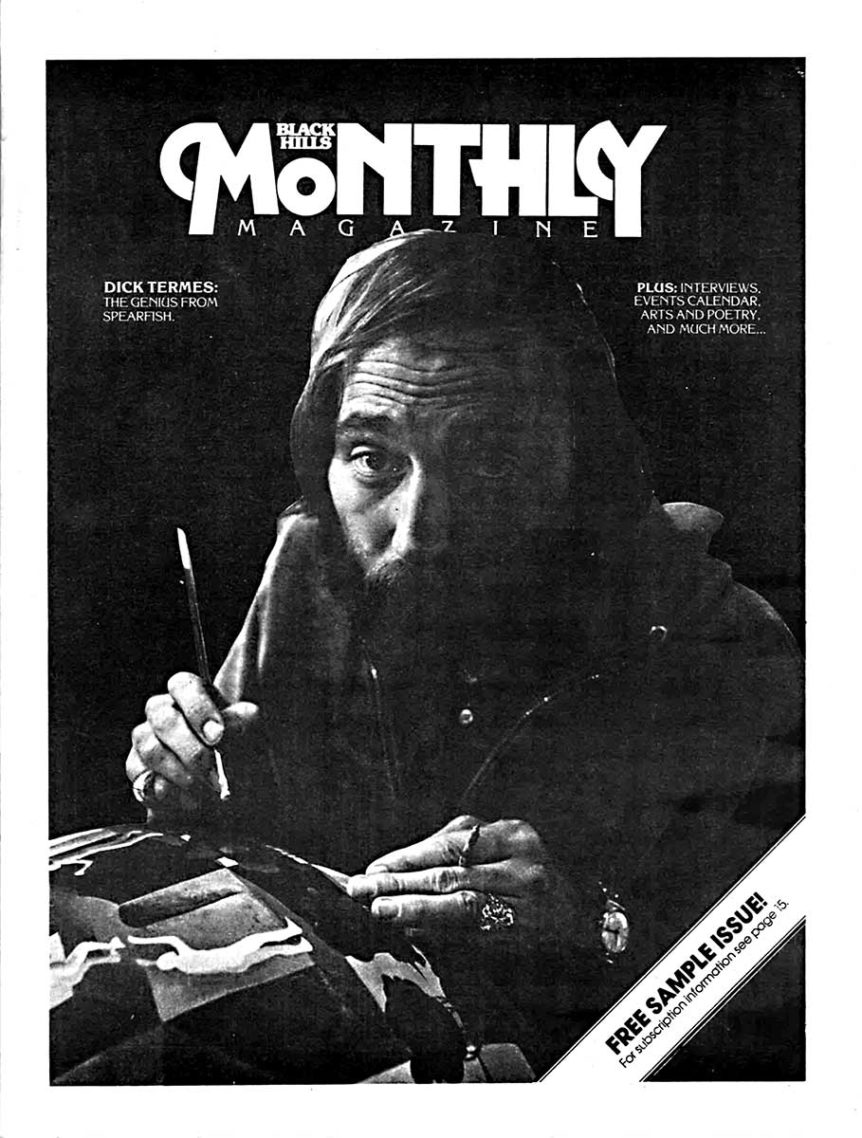

Drive south two miles on Christensen Road for the answer; On the left hand side of the road, in a grove of trees growing on some fine bottomland, sit two geodesic domes, a large one and a small one. Behind the domes, up the hill a way, you will see what looks like a six foot sphere with a painting covering its entire surface. And the domes are the studio and home of painter Dick Termes, his wife Markie Scholz and their infant son Lang.

Although the appearance of the Termes spread indicates the presence of a mind that marches to the beat of a different drummer, if not a different parade entirely, Dick Termes does not look like the traditional wild-eyed genius artist. (He has both his ears and no fancy cravat.) On the contrary, Termes is most likely to be found wearing a nondescript, unfashionable, one-finger, button-down shirt of early sixties vintage (“Well geez, it’s almost good as new!”), a faded pair of jeans complete with hole in one knee and a pair of cowboy boots he really did buy in high school. Dick Termes is thirty-eight.

Perhaps his only sartorial concession to eccentricity is the Termes hat – a crumpled, wide-brimmed affair decorated with bright beads and dark stains of undetermined origin. He has the build of a runner (which he is), the beard of a logger (which he is not), and the haircut of a man who thinks about barbers at irregular intervals.

In short, if you saw Dick Termes on the street you probably wouldn’t point and stare. If you saw him at home you might not even notice him for his studio-home demands full attention. But don’t be fooled by Termes’ nondescript appearance.

Back to home. Outside, his geodesic domes are covered with cedar shake shingles. Inside, they are filled with combinations of fantasy, geometry and motion. The big dome, thirty feet in diameter, serves as the living space. It contains finished works which include traditional, flat paintings, and, about thirty Termespheres.

A Termesphere (Ter-mi-sphere) is a globe or ball with a painting covering the surface. These spheres hang from the ceiling of the dome at various heights; most of them spin slowly, powered by small, silent, electric motors. Up a narrow, spiral staircase you find the master bedroom and baby Lang’s nursery. A gently rising stairway leads through a tunnel-like hall to the smaller, eighteen foot dome that serves as studio. It is the home of works in progress, files full of notes, brushes, palettes, paint pots and tubes, the various paraphernalia common to painters and bunches, of tennis ball size spheres and cardboard polyhedra – rough ideas for Termespheres past, present and future.

The Termesphere is the heart of Termes’ work. Termespheres are combinations of surreal fantasy and geometric design. They range in diameter from eight inches to six feet and represent both subconscious, free association and pains-taking planning. The subjects include people; usually faceless, dream figures; weird landscapes; buildings; Escher-like rooms and abstract shapes that twist and curve all over the surfaces of the mini-planets.

And always, there is the six point perspective. For Joseph Meier it is a life-size Calvary. For Gary Muledeer it is a typewriter on the shoulder. For Dick Termes it is six point perspective. Compared to six point perspective, Christus portrayals and rock concert humor are easy to explain.

Basically – very basically – imagine a cube. (As a matter of fact, you are warned to keep your imagination in gear from here on.) Now, in a simple drawing of a cube there are three sets of parallel lines. When one set of these parallel lines merges to a vanishing point on the horizon the result is simple, one point perspective.

When two sets of parallel lines merge at two separate vanishing points on the same horizon you have two point perspective. You’ve seen this effect before when the walls of a building recede into the distance (getting smaller) in different directions. Consider, then, the parallel lines on the side of a cube. Extend them downward to a third vanishing point. Voila! Three point perspective. This effect is best visualized if you think of looking at a skyscraper viewed from high in the air. The two walls fade into the distance and the bottom gets smaller and smaller as it gets farther away from your eye. The plot thickens.

So far we have used straight lines to extend to our vanishing point. And remember that the cube has three sets of parallel lines. When we arrive at four point perspective, an interesting phenomena occurs. To achieve the fourth vanishing point, one of the three sets of parallel lines must be extended through the optical center in both directions. The optical center is the center of the cube. However, when this is done Mr. Straight Line, whom we have known and loved in perspective since the days of DaVinci, deserts us. Here, a straight line just doesn’t look right. But. a gentle curve does quite nicely. Why? Termes explains:

“When two or more lines are projected both directions to two given vanishing points, at least one of them must be bent. Only a line through the exact -optical center can be straight. Parallel lines that don’t run through the center, but vanish at the-same point, must turn a corner, overlap, or bend. The most natural effect comes with a gradual curve. A fish-eye lens or a reflection in a shiny Christmas tree ball are common examples of lines of perspective that blend to a vanishing point.”

This same bending phenomenon holds true for the fifth and sixth point of perspective, but four points is the limit that can be drawn on a flat piece of paper. Five and six point perspective can only be demonstrated in space. By the time we have six vanishing points – north, south, east, west, up and down – the lines leading to the vanishing points all look proper only when curved! (Are you still there?)

Says Termes, “The only way to see this could be possible would be to see it from within a cube.” Having the eyes of two flies would help, too. Termes continues, “To hold the perspective from within and to view it from without leads to many exciting images and ideas.” Indeed.

What happens to our cube as the lines become more curved, and as each of its six points of perspective approach the middle of its adjacent side? It becomes more and more sphere-like. When the cube becomes a sphere and a drawing based on the perspective of the cube is projected onto the surface of the sphere, _we have, in the artist’s own words, a perfect example of seeing from outside what was conceived from the inside of the cube.” Heady stuff, but you were warned not to let the sixteen-year-old J.C. Penney button-down shirt fool you.

The result of all this projection is a completely spherical fish-eye lens, which produces some striking effects. For example, if you stare at a Termesphere for a minute or two as it revolves, it will suddenly appear to change the direction of its rotation, or just as suddenly become concave instead of convex.

These visual illusions are interesting, but the essence of Termes’ work lies beyond tricks on the eye. Organization and a combination of the cognitive with the subjective give art meaning for Termes. “At the University of Wyoming I was doing very organic work, and I was getting bored with my art. Studying under Victor Flack at Wyoming was a turning-point for me. He taught me to know why I was doing what I was doing and to organize my mind.” And organize it Termes did.

The organizing influence of Buckminster Fuller is unmistakable in Termes’ work. Fuller is best known for his pioneering work with the geodesic dome, two fine example of which form the Termes studio-home environment, but Fuller’s philosophy of synergy plays a more important role in Termes’ approach to his art. “Synergy,” says Webster’s New Twentieth Century, “is the simultaneous action of separate agencies which, together, have a greater total effect than the sum of their individual effects.” And that is the point of the Termesphere. “I want a painting to be organized as a human being is organized. Maybe that’s what beauty is.”

Aha! There is a method to his madness. In geometric and mathematical relationships, especially those found in six point perspective, Termes finds a strong sense of the synergy and interdependence of man and his environment – of figure and ground. This theme carries over to the content of his work. Dick Termes is fond of mentioning the flip-flop effect. “I want to allow a ball to be a ball and a ball to be a hole at the same time. I find my own mind flip-flops between realism and surrealism, micro and macro…this is what Fuller talks about as being “in-ness and out-ness.”

The specific contents of Termes’ paintings range from abstract geometric shapes to surreal fantasy scenes, but the theme of the totality..of the yin yang relationship is omnipresent. The Termesphere he calls “Shelves of Reality” is loosely based on a legend of the Mohawk people. The legend tells of the people growing a tree from the sphere of the earth up to the sphere of the sky, where another world exists. In this painting Termes creates a central world of a checkered plain littered with geometric shapes and peopled by amorphous figures. Fantastic trees and structures reach up to the sky – another sphere world. Then, below the checkered plain, another sphere-world is teasingly revealed. And through a hole in the sky still another world is found. And between plain and sky yet another world. Shelf upon shelf of reality coexist, both independent from and dependent on each other.

Expanding your sense of reality is a crusade with Termes. “I want to teach people about total visual awareness… awareness with the eyes the same way a musician is aware of totally enveloping sound. My spheres are an effort to alert people to the spaces in their worlds that are beautiful in every direction.”

A Termesphere starts with a rough sketch on a polyhedron. In the case of most six point perspective spheres, the particular polyhedron used is an octahedron, or two pyramids – one upside down and the other resting on it, right side up. The points of the octahedron coincide with-the vanishing points. Lest things are sounding too simple, it must be noted that Termes sees no reason to limit himself to this particular design. The icosahedron’s twenty sides form twelve vertices and, of course, twelve vanishing points. Says Termes, “I feel that people would have more trouble relating to (these more complicated) systems. But as man’s mind expands with the space age, he will find it easier to accept the loss of the horizon and the earth-like six directions.”

So Termes continues his quest with tetrahedrons, hexahedrons, dodecahedrons and even – stand back – triakonta-hedrons! Once a rough sketch is completed on the many sided face of whatever polyhedron is being used, the work is transferred to a sphere made of Lexan plastic. “It’s what they make the astronaut’s helmets out of,” Termes tells anyone who asks. He seems to take a boyish pleasure in that.

And he takes pleasure in other pursuits. Deer hunting is a family tradition. Cross country skiing, running and tennis keep him in shape, and Termes plays a mean harmonica.

Dick Termes’ absent-mindedness is legend. Once, when being interviewed on the South Dakota Public Television show, Mosaic, the host of the show, Craig Volk,: asked Dick what the name of one of his spheres was.-Termes thought for a second and replied, in utter seriousness, “Gosh, I don’t know. What is the name of that one, Craig?”

How does a bona fide art-pioneer make a living in the Black Hills? Major galleries are hundreds of miles away, but, somehow, Termes supports himself and his family with his- craft. His credentials are impeccable, and that helps. He has advanced degrees from the University of Wyoming and the prestigious Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles. He’s had shows in Omaha, Denver, Los Angeles, San Francisco and in smaller communities throughout the west – especially in South Dakota. Termes is a regular contributing artist to projects of the South Dakota Arts Council, and from time to time teaches color theory at Black Hills State College in Spearfish.

Dick Termes is known to many communities in the state as an organizer and expediter of community mural projects. He’s done fourteen of these, including a large outdoor mural in Spearfish.

That is how Termes makes his living in the Hills. And why does a bona fide art pioneer even try to make a living so far from so-called cultural centers? “Family is important to me. Both sets of my, grandparents made their homes within fifteen miles of Spearfish. I was raised here. I think everyone has his intellectual center, and, for me, it’s the Black Hills. I studied in L.A. for a couple of years and it seemed that I would get all my creative ideas when I came home for the summer. I could work on the technical stuff in the city, but I couldn’t think or function creatively. And now the Black Hills are attracting more and more creative people to bounce off of. ”

And the ideas keep flowing. Termes’ latest project is his patented Total Photo. Using a process he developed, he can photograph, from one point, a three hundred sixty degree (including up and down) photograph which is printed on Termes’ old friend, the icosahedron. Each Total Photo is actually a series of twenty photographs fitted together by Termes. Total Photos have been done of Mt. Rushmore, Lower Falls in Yellowstone, downtown Deadwood and Spearfish, Main Street Sturgis during the motorcycle races and other locations. In a Total Photo the viewer can see from the outside-what is photographed from the , inside – literally. But you definitely have to be there. Like so much of Termes’ work, the Total Photo guffaws at attempts to describe it.

And the growth process continues, too. Says Termes, whom many would consider an expert on color. theory, “I’d like to get my approach to color more organized. My work is all based in theory, but I usually get carried away.”

Dick Termes welcomes visitors to his studio-home. Just give a call first; he’s in the book. The sight of thirty surrealistic spheres hanging from the top of a geodesic dome is worth the drive. Each sphere represents six to ten weeks of concentrated thought, inspiration and work. Some are for sale, with price tags ranging from $750 to $4000.

And you’ll have the chance to meet the man who went to school with Gary Muledeer and carried spears for Joseph Meier – the Spearfish genius who stayed home.

Six Point Perspective Explained… Sort of.

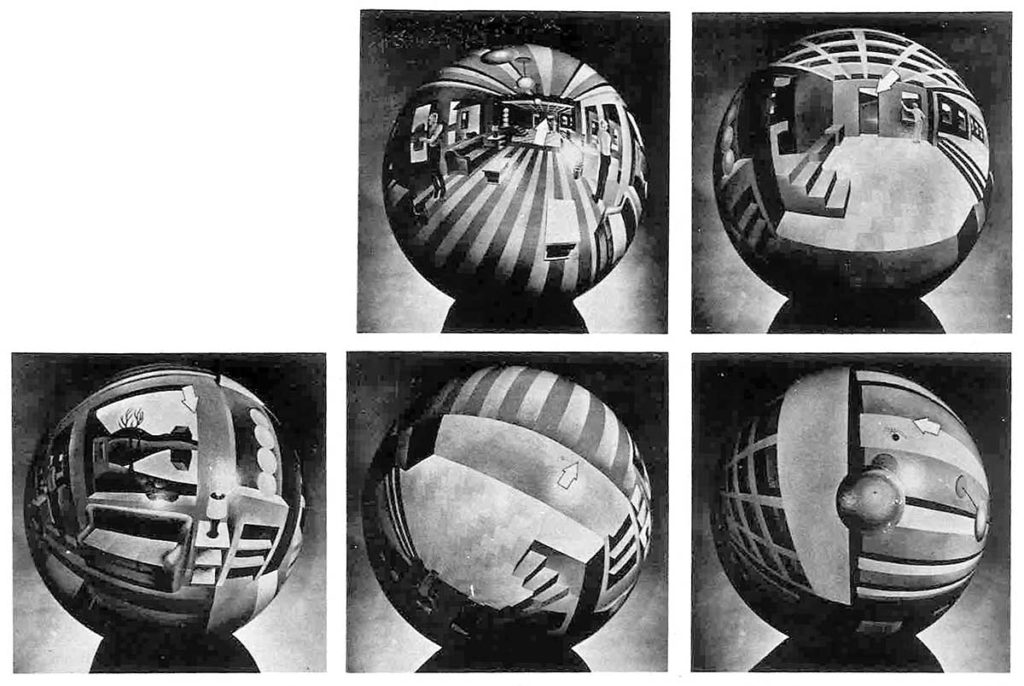

The only way to thoroughly appreciate a Termesphere is to stand before one as it revolves in space. Even then, the vanishing paints and the rigid grid structure upon which the painting is based are elusive; partly because of Termes’ hide and seek playfulness in design, but chiefly because our eyes and minds are unaccustomed to visual organisation an a round surface with twice as many points of reference as are possible on a two dimensional work.

Termes often has more than six vanishing points in a work (the extra few allow him to create space inside the surface). For simplicity’s sake, if any of this can be thought of as simple, we are presenting here a Termesphere photographed from six angles in such a manner that the six vanishing points are positioned just above and to the right of center (arrows).

The lines, remember, are not curved, but straight. The roundness of the sphere makes them appear curved in a two dimensional photograph.

Parallels with Einstein’s theory of curbed space are easily called to mind when studying Termes’ painting, and for this writer, a Termesphere is the most accurate visual aid imaginable when trying to grasp that visually impossible concept.

If the universe is positively curved, an astronomer with an impossibly powerful telescope could look around this curved spare into the distant past to a point where the back of his own head will exist billions of years in the future. The subject matter of the Termesphere illustrated here suggests just such an occurrence. Notice that the man, the stairways, the furniture. In fact all elements of the room are presented in two aspects, all drawn in relationship to six vanishing points.